In just over a month, the International Olympic Committee members will vote in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, on the site of the 2022 Winter Olympics. Their two choices: Almaty, Kazakhstan, and Beijing, China.

Only these two candidates remain after other bids from regions like Bavaria, Germany (centered in Munich), Graubunden, Switzerland (centered in Davos and St Moritz), Stockholm, Sweden, and Oslo, Norway, were felled by referendums.

That’s not a good sign for the IOC. Both bids have some problematic features, and are almost certainly not the ideal locations the organization was looking for.

While there are problems with the Almaty bid, to almost any reasonable person there appear to be far more, and more serious, problems with Beijing. Despite all of this, Beijing is the frontrunner.

That’s because it has the force of the Chinese government behind it. The IOC knows that the Chinese can deliver a Games. A Beijing Olympics would happen, without any major cost to the IOC except for bad publicity and a continued slide down from any moral high ground they might have left.

The Almaty bid closed part of its gap at the candidate city presentations in Lausanne, Switzerland, last week. But in the event that Beijing still comes out on top when voting is over, here’s an overview of six major issues that the Olympics would face – and examples of some of the misrepresentation and lies the bid committee says publicly when questions are brought up.

First, there’s the snow. As skiers, it is probably one of our main concerns. Will there be enough? Where will it come from? Zhangjiakou boasts about a meter, total, of snowfall each year.

The answer is, snow will come from water. But that leads to another question. What effect will that have on the regional water dynamics of a drought-prone region?

Then there’s air quality. It’s known to be terrible in Beijing. But organizers assert that air quality is great at the mountain venues. The problem is, that’s just not true.

Next up, how will spectators get to the mountain venues? At almost 200 k north of Beijing, travel times could be long. The bid committee touts a high-speed train connecting the clusters, but it’s becoming clear that this won’t solve all problems and could even be dangerous.

After the 2008 Olympics, it was clear that China followed through on few of their promises to improve human rights. Is there any reason to think that this time around will be different?

And finally, thinking long-term, what is the point of hosting a Games where winter sports are not popular and where snowmaking is so disruptive? Will the venues be used in the future?

Snow: Quite honestly, there isn’t much.

The weather is cold and it’s enough to blow snow, however, at least for alpine skiing. The Chongli area outside of Zhangjiakou has four alpine ski resorts which host, according to the bid committee, 1.5 million visitors annually. Nordic facilities have not yet been built.

On the ground, the area isn’t always teeming with skiers.

“The chairlifts are somewhat slow, but queues are rare and the slopes are mostly empty,” a review of the Wanlong resort, one of the biggest in the area, notes.

By comparison, the state of Vermont gets about 4.5 million ski visits per year, although that is based on ticket sales and it is unclear whether the Chongli numbers are from all tourists or just those who buy a lift ticket.

Looking at meteorological data, it’s hard to imagine the region becoming a real winter sports mecca without snowmaking.

“The total annual snowfall here can reach more than one meter,” Liu Jianjun of Chongli’s weather bureau told the press.

One meter!?

And yet:

“We have a 20-year history of hosting skiing events… Each year there is a 25% increase in the population taking part in skiing in Zhangjiakou,” Hou Lang, the mayor of the city, said in a press conference in Lausanne. “The temperature, wind speed, and mountain situations are ideal for hosting a Games.”

The bid committee’s strategy is to make and hoard snow. Already, resorts feature snow on the trails but brown forests and dry, frozen ground beside them.

“In addition to natural snowfall we have a very comprehensive plan to ensure the quality and quantity of snow,” Zhang Li, the venue manager, said in the press conference. “This plan is based on the combination of appropriate temperature, abundant water supply, and reliable existing snowmaking facilities.”

The IOC Evaluation Commission noted in their report that the resorts are already situated on the highest mountains in the region, so there would be no way to haul in snow from other locations. And as was shown in Vancouver 2010, temperatures can unpredictably rise during warm snaps and prevent snowmaking.

During discussions about the two candidate cities, experts reportedly testified that a 50-50 mix of manmade and natural snow was ideal, and that this was attainable with the Beijing bid. Two problems: most athletes would argue that actually a zero-manmade, all-natural snow base would be ideal, and secondly, it’s not clear that 50% natural is even realistic.

Siting an Olympic Games in a place with essentially zero natural snow seems like a big risk. Yet the IOC does not seem overly worried with this issue compared to others.

Water: On top of all of that, it appears that the bid committee does not fully understand just how big an undertaking it would be to make all of that snow. 16 million cubic feet of snow were reportedly stockpiled before the 2014 Sochi Olympics, where there was more natural snow to use as a base anyway.

It took over 140 gallons of water to make just one of those cubic meters of snow.

“The Commission considers Beijing 2022 has underestimated the amount of water that would be needed for snowmaking for the Games,” the Evaluation Commission wrote.

Zhangjiakou is in a notoriously arid region. There simply isn’t a lot of water available: just 383 millimeters per year, or 15 inches. The winter is the dry season, and Zhangjiakou receives less than five millimeters per month then.

The New York Times reported earlier this year that the region is home to water conflicts, which those in the western U.S. might find familiar.

“We can’t use it,” a farmer said of the scant rainfall. “It’s for others, not us.”

The small amount of water available is often sent south to Beijing, a major city which has priority over rural areas. It is now being used for snowmaking as well, and should Beijing win the 2022 bid the amount needed for snowmaking will only increase.

“The total amount of water used for the entire Games duration for snowmaking represents only 1% of annual available water supply in this area,” Zhang Li said in the press conference.

However, the Evaluation Committee had already made clear that they believed this estimate was incorrect. And in a region with barely any water, one percent can still make a big difference – just ask California.

Because of China’s controlling government and human rights problems, those suffering from further declines in water resources would certainly be the least affluent residents of the Zhangjiakou region. Pouring more effort into snowmaking would represent a further shift to focusing on an affluence tourist market instead of local dynamics.

Yet the bid committee insists that there’s nothing to worry about.

“To ensure an abundant the water supply, we have three sources of water,” Zhang Li said in the press conference. “One is the surface runoff which has been the sole source for the existing resorts for the last 20 years. The second source is large capacity reservoirs in 6 kilometers of the venues. The third source is that we will benefit from the already almost-completed National Water Transport plan, which is transferring an enormous amount of water from southern China to the north.”

That transport plan has reportedly cost as much as $80 billion, although detailed estimates are hard to pin down.

The bid committee also plans to recapture snowmelt and use it to blow more snow, but the Evaluation Commission wrote that the ability to do this had been greatly overestimated.

Air Quality: Beijing currently faces some of the worst air quality in the world. During the 2014 Beijing marathon, particulate pollution was at 400 micrograms per cubic meter; the World Health Organization’s maximum for healthy outdoor activity is 25. Most participants wore masks and many did not finish the race.

“In Beijing, the ice sports will all be in indoor venues,” Wang Anshun, the mayor of Beijing and the head of the bid committee, helpfully noted in a press conference.

Beijing is in the midst of a five-year action plan to clean up air quality, which is costing about $130 billion and features 84 specific action points.

“At present, the action plan is already achieving excellent results,” Wang said. “Major pollutants in this period have dropped by 17.7 percent as compared to last year.”

After the plan ends in 2017, there are already plans in the works for another five-year agenda leading up to the 2022 Games.

In fact, the bid committee used the prospect of improving air quality in a not-so-subtle attempt to guilt people into supporting the bid.

“This also will be a form of permanent legacy that will benefit the local people of the city and the region,” Wang noted.

In other words: how could you turn this bid down when it will improve quality of life for millions of people, and make the air that they breathe no longer able to kill them?

However, it’s worth noting that an IOC mandate to fix pollution problems has not always in the past led to pristine conditions. Air quality was still a problem at the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, even after much-publicized attempts to solve it by closing factories limiting the amount of vehicles in use. While vast improvements were made, pollution was still worse than in all but the most polluted U.S. cities and about six times higher than at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics.

Immediately after the 2008 Olympics, air quality worsened again, now to those levels seen during the 2014 Beijing Marathon. Improving air quality during the Games did not have lasting effects.

Another case of the IOC struggling to mandate pollution cleanup is in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Just a year before the 2016 summer Games, organizers are still struggling to clean up the water in the city. Last summer the IOC brushed off concerns, saying there was still time to clean up, but they now seem more alarmed, and at the recent Executive Board meetings in Lausanne demanded to see progress by the end of July.

Part of the Rio bid was a promise to reduce the flow of raw sewage into the sailing venue by 80%, but officials now acknowledge that will never happen. (More alarmingly, they say that the failure to clean up is irrelevant because the sewage poses no health risks to sailors.)

In other words, if the host city promises in a bid to clean up, the IOC has no real way to hold them to that promise. Statements by the bid committee about air quality do not mean that athletes won’t see significant health risks when they arrive in Beijing in 2022.

Finally, the bid committee says that at the two mountain clusters, air quality is ideal. However, while Zhangjiakou does have the best air quality in its region, it is still not good. In the next two days, for example, air quality is forecasted to dip into the “unhealthy” zone, with the definition “Everyone may begin to experience health effects; members of sensitive groups may experience more serious health effects.”

And local regulations cannot completely solve air pollution problems, anyway.

“Increased energy demand in winter coupled with seasonal weather patterns that can bring pollutants from other regions could create air quality issues across the Games zones,” the Evaluation Commission wrote.

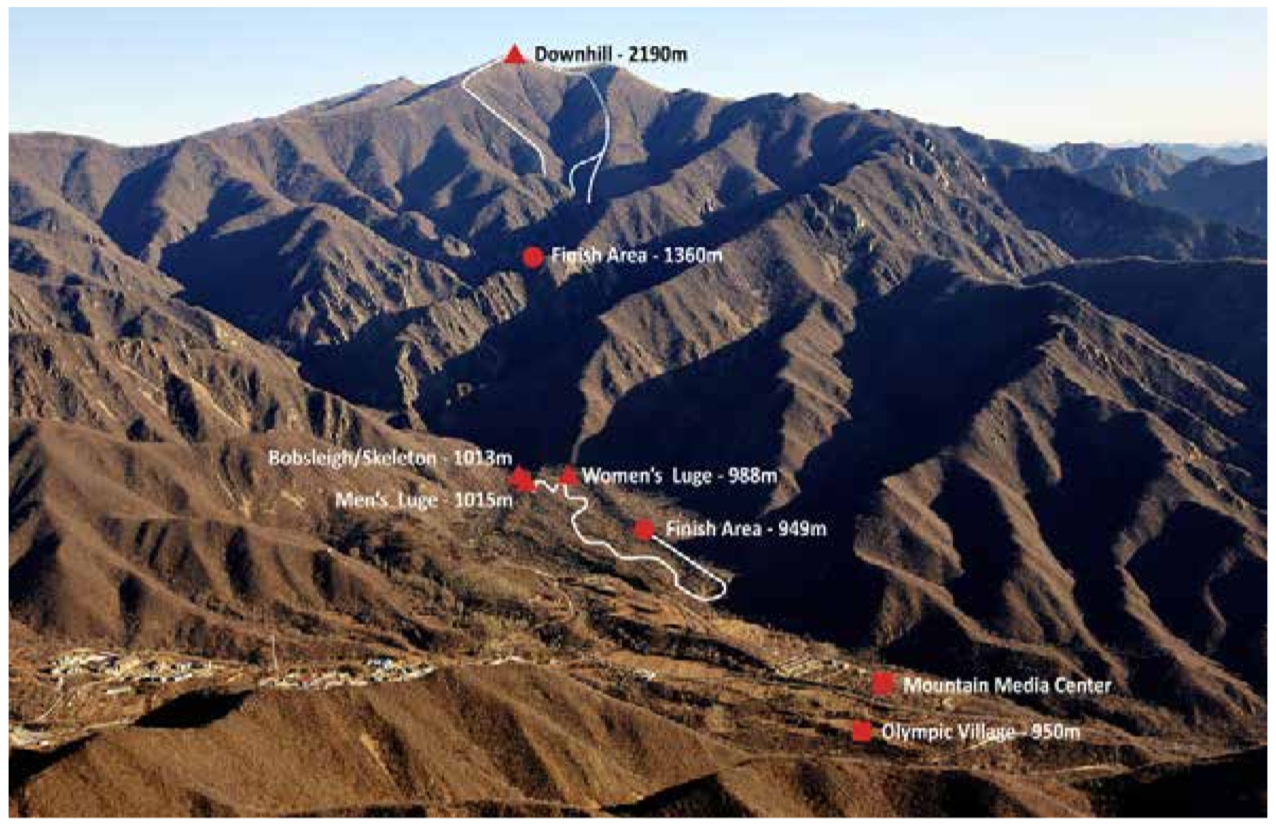

Distances Between Clusters: The Beijing bid will feature three clusters for sports: arena ice sports will be held in Beijing; nordic sports, freestyle skiing, and snowboarding in Zhangjiakou; and alpine skiing and sliding sports in Yanqing.

The bid committee promoted this three-zone idea as a benefit to athletes, who will not have to travel far to reach their venues or deal with the more general hubbub of a compact Olympic Games.

“To ensure the athlete experience, I know from my experience as an athlete that the most important thing is the performance in the Olympics,” said Yang Yang, a gold medalist in short-track speedskating and now an IOC member. “So to minimize the travel times would bring much benefit to the athletes. Having three zones will help the athletes with short distance to travel from the venues to the villages. It will be about 15 minutes, which is a very good benefit to the athletes.”

Aside from athletes, travel times for spectators could be quite long. The bid committee has proposed building a high-speed train system which it says would cut the time needed to travel roughly 200 k from Beijing to Zhangjiakou to 50 minutes.

There’s several problems with this. First of all, the bid committee left the expenses associated with building the network off the books, claiming that it would have built the railway anyway. That’s false, and cut the bid’s budget down to better compete against Almaty. Officials still refuse to reveal the actual cost of the railway.

Secondly, only when pushed did officials admit that actually, it would take longer than 50 minutes to travel between the venues. They admitted that 10 minutes should be added for waiting times to board the trains.

IOC members pointed out that that’s not all; after all, they have to get from hotels to the train stations, and then from the stations to the venues. Members complained that it would likely take them 90 minutes.

And for regular spectators who don’t receive the special treatment of IOC members, it’s likely to be a lot longer. This, along with the lack of a snow sports culture in China, contributes to the strong possibility to sports in the mountains facing empty stadiums. That doesn’t exactly make for the best athlete experience.

Already in 2014 in Sochi, Russia – a country where cross-country skiing and biathlon are successful and popular – seats were empty in the stadiums. This was likely due in part to the sale of multi-sport ticket bundles. A non-ski fan might go check out a sport they had a ticket to if it’s close; if it takes hours of travel each way, they might decide to stay in Beijing.

Lastly, with well-documented catastrophic train disasters and high levels of corruption hindering safety measures in China’s railway construction (you can find an incredible piece from the New Yorker here), does anyone really want to be on a high-speed train system where a crash, or even just a decrease in speed, by a train that departed just five minutes earlier could lead to a pile-up?

Human Rights

One of the biggest problems will provide nothing more than a repeat show from the 2008 Olympics. When Beijing won the bid for the 2008 Games, China boldly proclaimed that this was an opportunity for the country to improve their human rights record before they showed off to the world.

That certainly did not happen.

Hundreds of thousands of residents were evicted in the leadup to the 2008 summer Games in order to build new stadiums and infrastructure. The 2022 Games will use some of that infrastructure, so evictions should not be as numerous. But the Evaluation Commission report still estimates that thousands of people will have to be relocated.

And relocation is not something that China handles well. Houses were demolished and when residents tried to protest their evictions or appeal through the legal process, they were arrested, jailed, and sometimes beaten. Citizens have no choice in the matter, and are not provided the means necessary to re-make their life somewhere else.

“Compensation rates have rarely enabled affected people to relocate while retaining the same standard of living,” the Geneva-based charity Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions noted in a 2008 report. “Instead, residents have been forced to move further from sources of employment, community networks, and decent schools and health care facilities.”

Journalists who covered these issues did not fare well, with dozens of members of the media detained in the leadup to Beijing 2008. The Foreign Correspondents Club of China reported that 40% of foreign journalists covering the 2008 Games had experienced some sort of governmental interference, and that since then, conditions for foreign journalists have declined substantially.

Even while reporting on the bid for the 2022 Games there have been incidents. When two foreign journalists tried to visit the site of the mountain cluster and interview locals, government “minders” scared people away from speaking to them and inhibited them from visiting parts of the sites.

Those outside the media fared much worse. Before the 2008 Games, citizens who spoke to foreign media were sometimes beaten by police in retaliation. According to Human Rights Watch, Chinese who spoke out on a variety of issues, from human rights to the environment or corruption, were often arrested. In some cases activists were kept in prison for longer than the actual term they were sentenced to.

Then there’s the athletes. According to The Guardian, China forbid athletes with any history of dissidence or activism from participating in the 2008 Olympic or Paralympic Games. For instance, Fang Zheng, whose legs were crushed by a tank in Tiananmen Square in the 1989 massacre, was not allowed to compete despite having two national records in the discus.

There’s many other human rights issues in the country. Tibetan activists, for instance, infiltrated the candidate city presentation room in Lausanne last week to stage a protest of China’s occupation of the region. Before 2008, the Olympics were seen as providing a platform for Tibetans to speak out about their oppression. But nothing changed for the better.

If the 2022 bid is successful, that means seven more years of Free Tibet protests. That’s seven more years of the world being reminded that the IOC has chosen to host the largest, most lucrative sporting event in the world in a country that does not support the basic tenets of the Olympic movement.

“The goal of Olympism is to place sport at the service of the harmonious development of humankind, with a view to promoting a peaceful society concerned with the preservation of human dignity,” the second point of the Olympic Charter reads.

Legacy: One of the main points of the Beijing bid is that should they win, they will bring winter sports to “hundreds of millions” of people and provide a lasting legacy. This is how the bid committee appeals to IOC President Thomas Bach’s “Olympic Agenda 2020” plan.

Frankly, this seems unlikely. Even in countries which already have a strong winter sports culture, building new venues in places which are only moderately accessible to the general population has rarely been successful in building lasting legacies.

Let’s look back at Sochi, 2014. The snow and sliding sports venues will certainly never be used again for World Cup competition, and it’s not clear that they are seeing significant use from Russian athletes either. $51 billion were spent to build this Olympics and the mountain cluster is eerily empty. Resorts were operating at losses and renting luxury rooms for as little as $17 per night.

What about Vancouver, four years earlier? Canada has strong nordic, alpine, and freestyle ski programs. But the cross-country and biathlon teams no longer base training groups in the Callaghan Valley, a venue which sees little traffic. Canadian ski jumping and nordic combined struggle to even remain funded. Whistler Sport Legacies has more costs than profits, although some venues, such as the luge and bobsled runs, see a lot of use.

British Columbia and the Canadian Rockies have plenty of alpine skiing opportunities, which is perhaps the reason that the Whistler Creekside venue, which hosted alpine racing for the Olympics, has not seen any FIS-level competition since 2010. Lake Louise, Alberta, beckons instead.

Pragelato, the site of nordic racing at the 2006 Torino Games, has not hosted a FIS-sanctioned cross-country ski race since the World University Games 2007. The luge track has been dismantled for economic reasons, but the hockey and speedskating arenas have hosted other sports events as well as plenty of concerts.

Sestriere, where the alpine racing was held, is still a popular venue for Europeans, but hasn’t hosted a World Cup since 2009. And unlike most other snow sports venues used in 2006-2014, Sestriere was already a high-profile destination for both tourists and elite racers; the Olympics likely did not significantly affect its future.

So even in countries where there are plenty of winter athletes, developing new venues for the Olympics hasn’t contributed much to sports programs. Reaching fans is a different story, but there’s still not much evidence that hosting an Olympics seriously shifts the support for winter sports within a country long-term, aside from a brief flush of enthusiasm surrounding the Games itself.

And considering the high water cost of running the snow sports venues, it’s not clear that they would even be maintained in the long run, especially as climate change progresses.

The bottom line, and the Almaty comparison. Almaty faces some of the same issues that Beijing does.

Air quality is not great in the city, although it is of course nowhere near as bad as Beijing. Kazakhstan is not a model for human rights, and there is expected to be significant corruption should Almaty win the lucrative bid.

But on many points, Almaty comes out clearly ahead. For instance, many stadiums are already built and being used by both Kazakh athletes and to host international competitions like the 2011 Asian Winter Games or the upcoming 2017 World University Games. Almaty has snow, and it has winter athletes; it’s much more likely that the Games would have a lasting legacy improving sports opportunities for residents.

It is also a compact Games, with everything close together, and a relatively cheap one.

What Almaty lacks is the slick, powerful, marketing machine that Beijing has already put into place. Should Beijing win, it will be a clear message that money, financial stability, and glossy PR lines matter more to IOC members than the actual tenets of the Olympic charter.

Chelsea Little

Chelsea Little is FasterSkier's Editor-At-Large. A former racer at Ford Sayre, Dartmouth College and the Craftsbury Green Racing Project, she is a PhD candidate in aquatic ecology in the @Altermatt_lab at Eawag, the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology in Zurich, Switzerland. You can follow her on twitter @ChelskiLittle.